Egypt is an epic travel destination, transfixing the world with its pyramids, tombs, Nile River, and King Tut’s legacy. As home to the only remaining of the 7 Ancient Wonders of the World and the cradle of civilization, the country has a hypnotic hold on my imagination, so I set out to explore both mythical and modern-day Egypt. As a woman traveling alone in the Middle East, I joined up with Cairo Transport & Touring, based in Cairo, for a ten-day trip exploring Cairo and archeological sites on a Nile Cruise.

I flew into the Cairo International Airport, an international gateway city to Egypt, home to 21 million residents. Cairo is the capital of Egypt, with the largest metropolitan area in the Middle East, and the ideal starting point for exploring the country.

The Giza Pyramids inspire awe worldwide, but photos don’t convey the surreal experience of visiting them. The pyramids reside west of Cairo at the edge of the Sahara Desert. The archeological site holds nine pyramids built around 2580 BC and is the oldest and only surviving of the 7 Wonders of the Ancient World.

To put the pyramids in historical context, consider that Egypt’s story begins in 3001 BC with the union of upper and lower Egypt by the first pharaoh Menes. He founded the ancient Egyptian capital called Memphis in the north. Thirty Egyptian dynasties followed and ruled until 332 BC, when the Greeks arrived. Egyptian rulers from the 3rd to 6th dynasties built pyramids as burial monuments representing the primeval mound Egyptians believed was the world’s origin.

The Great Pyramid, King Khufu’s tomb, is the largest on-site, towering 481 feet and made of 2.3 million stone blocks. The Cheops Pyramid has interior burial chambers open to the public. You can go inside the pyramid for an extra ticket, but there isn’t much to see inside the small space with low ceilings. You won’t see any hieroglyphics inside the pyramids because Egyptian pictorial writing started in the 5th dynasty. The pyramids’ lower levels consist of granite from quarries in Aswan that traveled by the Nile more than 550 miles, and the upper levels consist of limestone.

A camel ride tops my travel bucket list, and the rides at Giza Pyramids are the real deal. You climb on the camel from the ground, not an elevated platform, and a camel handler holds the reins and walks the camel with you. The camel rides aren’t a fixed price, so use your negotiating skills and be aware of “upcharges,” where camel handlers will ask for more cash to take your picture. It’s a popular shakedown you can avoid by getting your traveling companions to take your photos. Overall, the experience is well worth it.

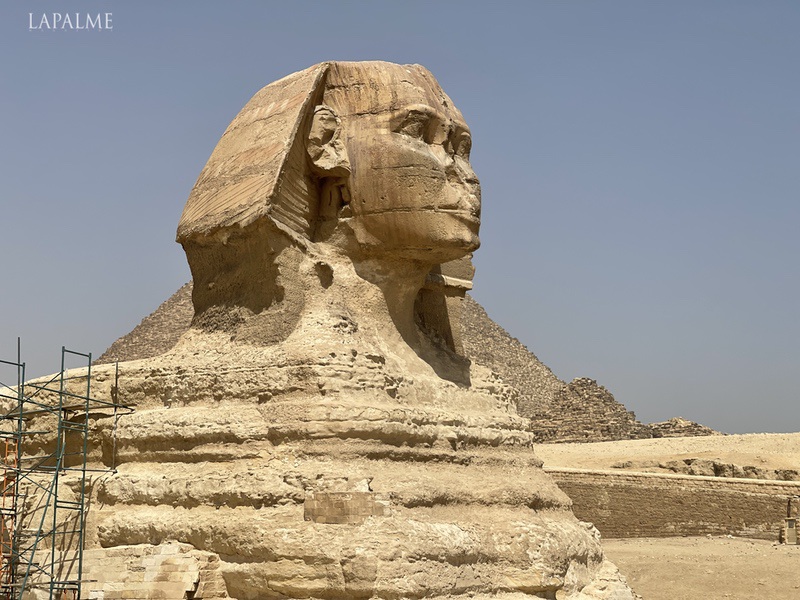

Next to the Giza Pyramid complex lies the Great Sphinx of Giza, the most famous and oldest of Egypt’s Sphinxes. The Sphinx, carved out of limestone during the 4th Dynasty, about 2620 BC, depicts King Chephren’s head and a lion’s body. The Temple of the Valley next to the Great Sphinx is where Egyptians mummified the bodies of their dead royalty.

For an up-close look at the largest collection of Egyptian royal mummies, I head over to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, battling Cairo’s chaotic traffic to get there. The museum opened in 2021, and one of its biggest draws is The Royal Mummies Hall.

Here you can see 20 Royal Mummies, 18 Kings, and 2 Queens, most notably Queen Hatshepsut. Ancient Egyptians expressed their reverence for the afterlife in art, architecture, and customs. The museum holds hundreds of objects that depict their beliefs about life and death.

Unlike the voluptuous bodies depicted in many European masterpieces, I’m struck by how ancient Egyptians painted the human form as svelte and sexy, wearing revealing fashions, elaborate jewelry, and dramatic makeup. My guide, Amir, explains why: “In Egyptian art, you never see somebody ugly or overweight. Everybody looks perfect. You see the kings wearing garments that show their legs and muscles. The ladies are wearing tight dresses to show off their beautiful bodies. Egyptians depict the human body from the profile. They show the face in the profile but the full eye and never show the belly button. This is not a mistake in art. Egyptians want to show every organ in the body in the most flattering way,” Amir says.

The rise and fall of many empires influenced Egypt’s diverse culture and storied history. The Greeks, Romans, and Arabs all left their mark, beliefs, and ways of being. Egypt was home to some of humanity’s earliest artists and architects and one of the first populations to chronicle their lives in a pictorial language called hieroglyphics.

The Egyptian Museum, located in Tahrir Square, the center of downtown Cairo, chronicles six thousand years of Egypt’s cultural history. The neoclassical structure opened in 1902 to protect, preserve and prevent the export of Egyptian antiquities. One of my highlights was the King Tut collection of jewelry and precious objects, including the young king’s iconic Golden Pharaoh mask, unearthed in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

In 2023, the Egyptian government plans to open the new Grand Egyptian Museum near the Giza Pyramids, making it easier for tourists to travel between the sites. For the first time, the Grand Egyptian Museum will display King Tut’s entire treasure collection alongside artifacts throughout Egypt’s history, from prehistoric times to modern-day culture.

I ended my time in Cairo with a shopping trip to Khan El Khalili bazaar, a 14th-century market located in the Islamic district of Cairo. Here, shopping is a sport, so be prepared to haggle over prices. If you are looking for souvenirs, Khan El Khalili is a great place to shop; however, if you are looking for handcrafted products, there are better sources than the bazaar for artisan-made items. Many booths sell similar merchandise, often mass-produced elsewhere.

Beyond the Pharaohs, temples, and tombs, Cairo’s fascinating religious history influenced its art, culture, and customs, from Egyptian pagan gods to Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Muslims first arrived in Egypt in 640 BC. Today, they comprise 85% of Egypt’s population, a demographic that defines the country’s cultural identity and way of life. The majority of Egypt’s Muslim population practices the religion of Islam. I visited Egypt during Ramadan, the Islamic holy month, which offered a unique window into the local culture. Ramadan is a time of festive energy in the streets and stores as the faithful shop for decorations, Eid al-Fitr gifts for loved ones, and unique ingredients to prepare the home and meals. “At sunset, Egyptians will have their Iftar ( the Breakfast ), so the streets of big cities, especially Cairo and Alexandria, will be jammed with traffic as people rush to get home before Iftar, ” says Mustafa Seif, Vice President of Cairo Transport & Touring.

Each morning, I wake up to Muslim chants of call to prayer from nearby mosques. The city comes to life as the faithful head to mosques to pray and street vendors begin opening markets and shops. Several of Cairo’s iconic mosques welcome visitors when not holding prayer services. These stunning domed structures dot the skyline with their towering minarets. Cairo is known as the city of one thousand minarets, mosque towers where prayer callers issue chants.

The Mohammed Ali Mosque has the highest minarets in Egypt, two that each tower 276 feet. The Turkish-style mosque resides within the walls of The Citadel of Saladin, a medieval defense fortress that housed Egypt’s rulers and state administration. The Mohammed Ali Mosque is nicknamed the “Alabaster Mosque” for the marble paneling on its interior and exterior walls. Inside, the central dome drinks in light, illuminating the prayer floor below, and walls and ceilings showcase intricate Islamic geometric designs.

My tour guide Amir gathers us to sit in a circle under the Mosque dome to chat about Ramadan and his religious beliefs. “The point of Ramadan is to feel the same feelings as poor people and to appreciate and thank God for what we have. We fast for self-control and abstain from bad behavior and desires. You have to be very spiritual during the fasting hours. Restaurants invite people to eat for free, and people waiting in the streets will throw you food and drink,” says Amir, who was fasting during our long, action-packed days, often in sweltering temperatures of 100 degrees or more. During the fast, Muslims are prohibited from eating or drinking anything, not even water. If Amir was hungry or thirsty, he never showed discomfort, inspiring my admiration for his self-discipline and stamina.

“We pray five times daily at 5 am, noon, 3:30 pm, 6:15 pm, and 7:30 pm. Ideally, we pray as a group in a mosque. If you are working or can’t pray during those times, you can make up for the missed prayers at the end of the day. We read the Quran and recite passages during prayer, which lasts about five minutes. Many Muslims bring a small carpet and place the carpet facing Mecca to pray,” Amir explains.

I appreciated Amir’s candid conversation with us Western tourists about his faith. It’s moments like these, when we can better understand each other and find common ground, that reminds me why I travel—when you know more, you fear less about people and places different from your world.

Outside the mosque, a large brass clock tower keeps time. It was a gift from King Louis Philippe of France to Muhammad Ali Pasha, who had gifted France one of two obelisks at the entrance of Amon temple of Luxor. That obelisk now stands in Place de la Concorde in Paris, the famous traffic circle at the bottom of the Champs-Élysées.

Christianity and Judaism also influenced Egypt’s culture, co-existing in Old Cairo. The area originated as a walled palace city founded in 969 BC by the Fatimids, an Arab dynasty that ruled most of North Africa. Today, museums, mosques, churches, and the famous Khan el-Khalili Bazaar populate Old Cairo.

Some of Egypt’s oldest and most important churches reside in Old Cairo atop the ruins of The Fortress of Babylon, built in 30 BC. You can see the exposed foundations of the Roman fortress at The Hanging Church, a Coptic Christian Church, built in the 5th century, 45 feet above the ground. Intricately carved Coptic Christian art and religious icons adorn the walls and ceilings. The Church of St. Sergius and Bacchus is nearby—a short walk along a narrow pedestrian lane. St. Sergius was built in the 4th century as a church with special religious status among Coptic Christians who believed it was a hiding place for the Holy Family. The church invites visitors into a cave below the sanctuary that sheltered the Holy Family from King Herod of Palestine, who wanted to kill the baby Jesus.

A Nile cruise is the ideal way to experience Egypt’s archeological treasures. From Cairo, I fly to Aswan to board a four-night cruise on the Blue Shadow. Amir is an Egyptologist who accompanied us to all archeological sites, sharing expert insight and fascinating stories about each site’s history, legend, and lore.

Along the Nile, I encounter ancient temples and tombs, rather than pyramids, because many originated after the 6th Dynasty when pharaohs began building underground mausoleums to protect their burial sites from grave robbers.

While in Aswan, Egypt’s southernmost city, located about 600 miles outside Cairo, I visited the Philae Temple complex, built by the Greeks in 285 BC, to honor the Egyptian goddess of love, Isis. The Greeks built the Philae complex during the reign of the Ptolemy family, the last dynasty of ancient Egypt, known as Egypt’s Greco-Roman Period. The Isis Temple holds the last known hieroglyphic writing dating to 394 AD, the Graffito of Esmet-Akhom carved on a temple wall. The temple of Isis was one of the last ancient Egyptian temples to remain active after the arrival of Christianity in Egypt.

The following day, I took a three-hour bus ride to Abu Simbel to witness a fascinating feat of ancient engineering. King Ramses II built two temples at Abu Simbel, one for himself and one for Queen Nefertiti. Four massive seated statues of King Ramses II, one of Egypt’s longest-ruling pharaohs, adorn his temple façade. The Egyptians built Abu Simbel as a time-keeping temple along the sun’s axis. Twice a year, on February 22nd and October 22nd, the sun’s rays enter the temple, cross the main hall, and illuminate the innermost statues. Inside, you can see well-preserved, colorful paintings and detailed stone carvings.

Both Abu Simbel and Philae Temple were relocated stone by stone from their original sites as part of an extensive relocation project by the Egyptian government working with UNESCO to save the monuments from flooding created by the High Dam’s construction in Aswan.

That evening, as the sun set, I visited the double temples of Kom Ombo, which serve two gods— Sobek, the crocodile god, and Horus, the falcon-headed god. The Greeks built Kom Ombo along a stretch of the Nile once infested with crocodiles. Legend has it that by honoring Sobek, the Egyptians could gain protection from the crocodiles, but they had to counterbalance worshiping an evil god with the good god, Horus.

At sunrise, a horse carriage arrives at the cruise dock to take me to the Horus Temple, winding through the streets of Edfu, as the town comes to life. The Greeks built the Edfu temple in 237 BC to honor Horus, the falcon god. It was lost to history, buried under sand until 1860 when a French archaeologist uncovered and restored parts of the temple.

I entered the temple through a massive gateway, standing 130 feet high with two tapering towers. Two giant granite statues of Horus stand on either side of the entrance. A courtyard surrounded by thirty-two columns leads to the Great Hall, supported by giant pillars adorned with ornate reliefs. The hall’s walls and ceilings display detailed depictions of Horus, astronomical signs, and hieroglyphics. His temple was an important place of worship until the Roman emperor, in 391 AD, banned paganism throughout the Roman Empire.

Our next stop is Luxor, home to one-third of the world’s monuments. Karnak Temple spans 247 acres and holds Egypt’s largest collection of temple ruins, developed over more than one thousand years by pharaohs, Muslims, and Christians. Karnak, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, chronicles 2000 years of ancient Egyptian history and architecture. The largest temple in the complex honors Amun-Ra, the god of sun and air. At its peak, Karnak was the largest and most important religious complex in ancient Egypt.

Luxor Temple resides near Karnak and holds one of two original 82-foot tall obelisks. The second obelisk now stands in Place de La Concorde in France, a gift from Egypt to France. Today remains of this vast complex include the colossal Great Colonnade Hall with 28 columns, ornately decorated by King Tutankhamun. The Avenue of Sphinxes, lined with more than 1300 stone sphinxes, connects Luxor and Karnak. It served as a processional road for sacred ceremonies and festivals. Ancient Egyptian Kings built the Avenue of Sphinxes over many years between the 18th Dynasty and 30th Dynasty, and in 2021, the Egyptian government restored and reopened it.

Next, we head to the Nile’s west bank to explore the Valley of the Kings, the burial site for Egypt’s New Kingdom pharaohs from the 18th to 22nd dynasties. Valley of the Kings is the site of the famous archaeological discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb. In 1922, archeologist Howard Carter discovered King Tut’s tomb buried under another tomb. King Tutankhamun was the boy king who ruled starting in 1332 BC for a decade before dying young. The excavation of King Tut’s tomb unearthed more than 5000 treasures, including a solid gold coffin, a bejeweled chest plate, and a golden death mask.

Walking through these tombs, I think about how the afterlife created an industry and economic engine in ancient Egypt. Tomb preparation began while the person was alive, employing artists, architects, craftspeople, laborers, and stonemasons. Together, craftspeople worked to create everything needed in the tomb for the afterlife, including jewelry, art, artifacts, and furniture.

We end our Nile cruise with a visit to the triple-terraced temple of Queen Hatshepsut, ruler of the 18th dynasty, at Deir el-Bahri on the west bank of Luxor. The female pharaoh ruled Egypt for 22 years after stealing the throne from her stepson upon her husband’s death. Legend has it that Queen Hatshepsut dressed like a man, claiming she was of divine birth. When her stepson reclaimed the throne, he destroyed and defaced Queen Hatshepsut’s monuments.

I say goodbye to Egypt with mixed emotions. The trip pushed me out of my comfort zone at times, given the language barrier and religious customs, but these experiences opened my heart and mind to another way of being and seeing the world. I discovered the timing of my trip during Ramadan offered a richer experience of Egyptian culture with celebrations, culinary creations, decorations, and design finds that surface once a year.

To discover more about Egypt, watch The Design Tourist travel show airing on major streaming networks and youtube.com/thedesigntourist.

- Exploring the Paths Less Traveled in Iceland - May 4, 2024

- Exploring Egypt From Cairo and Up the Nile - May 16, 2023

- MENDOCINO, CALIFORNIA : A DOWN TO EARTH DESTINATION - March 3, 2023